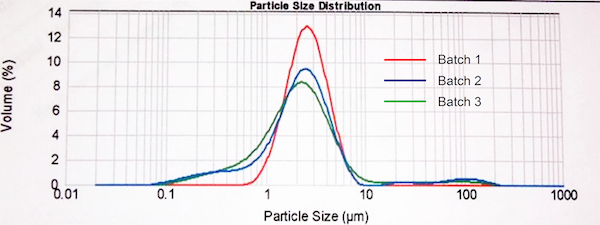

The majority of DPI formulations are micronized, which results in a relatively broad particle size distribution relative to alternative techniques such as spray drying. The figure below displays measured particle distributions from 3 batches of the same micronized active pharmaceutical ingredient. All have an MMAD close to 2 µm, but the very fine tail and levels of larger particles are clearly different in each case. No assumptions about the presence, or indeed absence, of an extra fine fraction, can therefore be drawn directly from a quoted MMAD without more detailed examination of the distribution.

Figure 1: The majority of DPI formulations are produced via a process of micronization and particle size distributions may vary considerably, even for materials with a closely similar MMAD.

Answering the question of whether any extrafine material present results in enhanced clinical efficacy for these existing products is tricky because to do that we need both to robustly characterize material in the extrafine region and to determine how much of the clinical effect can be attributed to it. While there can be technical difficulties in evaluating the exact contribution of the extrafine component, the evidence we’ve seen suggests that formulations containing extrafines deliver superior efficacy and specific outcomes such as greater asthma control and consequently an enhanced quality of life.

Q: How do we need to change our analytical approach if we want to focus on extrafine particles?

A: If we want to begin looking at the extrafine region in more detail, we may need to think about modifying the analytical approach that we currently use, because it has certain limitations.

The Anderson Cascade Impactor (ACI) and Next Generation Impactor (NGI) are, of course, the workhorse impactors for testing OIPs. They have been optimized, most especially the NGI, for studying particles from 1-5 µm in size and they both have 5 stages with cut-off diameters in that range, to provide the necessary resolution. However, when it comes to the sub two micron range, neither impactor provides detailed information because much of the extrafine part of the distribution is captured en masse on the last filter plate.